Chart Of Accounts For The Small and Medium Business A Complete Guide

FloQast™ Ops is a workflow manager that extends the power of FloQast Close, providing greater control over accounting operations and optimizing workflows across every function.

FloQast™ Ops is a workflow manager that extends the power of FloQast Close, providing greater control over accounting operations and optimizing workflows across every function.

Effective accounting practices demand a litany of skills and knowledge, and fiscal acuity is especially critical for time and resource-challenged small- to medium-sized organizations. Every buck counts and organizing and reporting on them within a cogent General Ledger not only provides insight and discipline but results in improved processes that impact practical outcomes such as regulatory compliance. Enter the Chart of Accounts, aka COA, for our current consideration, as a key metric of financial health.

A COA is a listing of all the financial accounts in a company’s general ledger (GL). They are grouped into categories that correspond to the structure of an organization’s financial statements. These GL accounts are used to categorize every financial transaction a company makes and offer even an outsider a holistic view of an organization’s assets, expenditures, and income, all in a single place.

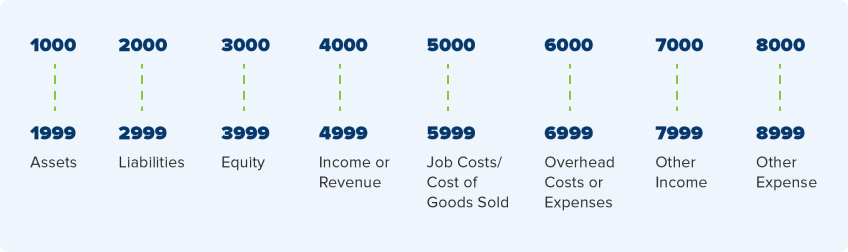

The chart itself consists of a list of numbered accounts, utilizing a name and a short description of what is included in that specific account. Per Freshbooks, these top-level descriptors can be simply viewed as follows:

Each account is assigned a “type” that identifies how a transaction is to be coded, indicating where it should appear in the financial statement. Most software applications offer a multitude of options and categories for the account type and having these set up accurately is critical to financial statement accuracy.

This represents a more specific drill-down of the Account Type, for a supplementary and highly detailed view of the entry across a broader category, such as Fixed Assets. In this case, it identifies the exact type of Fixed Asset being referenced.

Not always employed, this designation is used to control the order of accounts as they appear in the financial statements and can be beneficial in making them generally simpler to decipher and more actionable.

There is a generally accepted numbering structure for the accounts, so everyone’s accounts appear in roughly the same order and with similar numbering. Account numbers can be appended with three- or four-digit indicators to include added data to signify divisions, parts, products, etc. These are created depending on business composition (large, small, complex, simple) or how detailed its transaction descriptions may need to be.

A COA is designed to provide a view of an organization’s financial situation and health, using a delineated means to separate assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenditures. It assists with management reporting and is critical for meeting the demands of regulatory compliance. It is also crucial for business decision making and course correction, especially when structured to accurately portray differentials such as product sales vs. product returns, or salaries vs. overall productivity. The goal, again, is an accurate representation of overall financial health.

While flexible in its codification, most organizations choose to utilize a common numerical identification scheme. This can include multiple facets based on specific business needs. Here is a sample list of account numbers to show the de facto standard setup and numbering:

The accounts in the list provide the basic structure for an organization’s financial statements and GL. They are customized to provide the information required for needed visibility, reporting, and compliance. The common best practice categories (usually five) follow. Frequent changes to the numbering structure are not generally

encouraged as they can cause confusion, especially if not executed on a regular schedule, such as on an annual basis only.

These “buckets” correspond to different reporting statements, which are generally split to include the balance sheets, income statements, and any work in progress reports. Here the links show examples using a construction company as the business example.

While every COA will differ, there are some basic categories that most organizations will want to include, or at least consider, tailored to the specific nature of your business.

Bank accounts, typically checking and savings accounts.

Bank accounts, typically checking and savings accounts.

Accounts receivable are the amounts owed to you for products provided or services

performed.

Accounts receivable are the amounts owed to you for products provided or services

performed.

Retention receivables are the amounts customers are holding until work is completed.

Retention receivables are the amounts customers are holding until work is completed.

Assets your organization owns (usually physical, but not always- think patents,

trademarks, and software) such as equipment and real estate that assist in creating

your product or service.

Assets your organization owns (usually physical, but not always- think patents,

trademarks, and software) such as equipment and real estate that assist in creating

your product or service.

Underbillings are entries made when you have billed for less than you have

completed (otherwise referred to as percent complete income recognition)

Underbillings are entries made when you have billed for less than you have

completed (otherwise referred to as percent complete income recognition)

Inventory such as pre-paid materials, supplies, and parts kept on hand.

Inventory such as pre-paid materials, supplies, and parts kept on hand.

Customer deposits and down payments including any interim payments (such as

using a payment on completion of agreement method).

Customer deposits and down payments including any interim payments (such as

using a payment on completion of agreement method).

Accounts payable are the typical amounts you owe to vendors for raw materials or

parts, needed equipment, and any subcontractor-related services.

Accounts payable are the typical amounts you owe to vendors for raw materials or

parts, needed equipment, and any subcontractor-related services.

Retention payables are the amounts you owe to vendors held until work is completed.

Retention payables are the amounts you owe to vendors held until work is completed.

Assets your organization owns (usually physical, but not always- think patents,

trademarks, and software) such as equipment and real estate that assist in creating

your product or service.

Assets your organization owns (usually physical, but not always- think patents,

trademarks, and software) such as equipment and real estate that assist in creating

your product or service.

Loans, including any company or project notes that are outstanding current liabilities.

Loans, including any company or project notes that are outstanding current liabilities.

Shareholders’ equity (this may be negative or positive).

Shareholders’ equity (this may be negative or positive).

Overbillings are amounts owed when you have billed for more product/service than you

have completed (aka percent complete income recognition).

Overbillings are amounts owed when you have billed for more product/service than you

have completed (aka percent complete income recognition).

Retained earnings are company profits or losses from the previous fiscal year.

Retained earnings are company profits or losses from the previous fiscal year.

Amounts owed via employee expense accounts.

Amounts owed via employee expense accounts.

Sales, including income derived from the delivery of a product or service.

Sales, including income derived from the delivery of a product or service.

Interest income such as earned interest on bank accounts or other investments.

Interest income such as earned interest on bank accounts or other investments.

Over and under billing adjustments.

Over and under billing adjustments.

Labor costs may include such items as salaries, employee benefits, and any employerresponsible

taxes.

Labor costs may include such items as salaries, employee benefits, and any employerresponsible

taxes.

Material costs such as raw materials or parts needed to complete the finished

deliverable.

Material costs such as raw materials or parts needed to complete the finished

deliverable.

Subcontractor or non-employee expenses required.

Subcontractor or non-employee expenses required.

Equipment costs covering both rental and/or the operation of owned equipment.

Equipment costs covering both rental and/or the operation of owned equipment.

Administrative costs including labor and necessary operational software.

Administrative costs including labor and necessary operational software.

Office expenses that cover building

rent, office supplies, and other

operational needs.

Office expenses that cover building

rent, office supplies, and other

operational needs.

Taxes, such as business income tax

and sales tax.

Taxes, such as business income tax

and sales tax.

Insurance of all types such as liability,

workers comp, and vehicle.

Insurance of all types such as liability,

workers comp, and vehicle.

Vehicle costs including expenses related to maintenance and fuel.

Vehicle costs including expenses related to maintenance and fuel.

Mobile phones and the cost for both equipment and associated service contracts.

Mobile phones and the cost for both equipment and associated service contracts.

Sample Chart of Accounts are readily available for upload

from the Internet, or you can establish your own using

standard default numbers and customized sub-designations

for account types.

See the list earlier in this document for the specific macro-designations. That means, in most cases, all your asset accounts will use the number 1, followed by four numbers (1-XXXX), while your liability accounts would start with the number 2 (2-XXXX), and so on through the numeric list. This is a practical structure for businesses that manufacture or sell products and is a good fit for those looking for added specificity in their chart of accounts structure. Again, using the multiple three- or four-digit sub-account designations will provide more in-depth transaction tracking and overall fiscal transparency.

While the chart of accounts can be similar across like businesses, every COA should be unique to your business. Questions to ask include:

What do I want to track in my business?

What do I want to track in my business?

How do I want to organize information to best see my results and refine my strategy?

How do I want to organize information to best see my results and refine my strategy?

The COA is intricately linked to an organization’s financial statements, as it provides the aggregate data necessary to create them. Each one of the accounts in your COA will show up in your financial statements, and the COA directs where they should appear, i.e., whether they should be in the balance sheet or income statement. If not set up properly, subsequent financial statements will be rife with errors and misinformation.

Financial statements consist of the written records that reflect the state of the business, its fiscal activities, and its overall financial performance. These statements provide the basis for fiscal review by multiple entities, including internal and external accountants and auditors, existing and potential investors, as well as governmental overseers and affiliated regulatory agencies, such as the SEC. These audits and examinations are performed to validate the accuracy and viability of overall financial operations, and the results are used for multiple purposes, such as tax calculations and investment evaluation due diligence.

An organization’s financial statements are those records that convey all its related business transactions, wellbeing and status, and the overall financial performance of the entity.

The balance sheet provides an overview of assets, liabilities, and stockholders’ equity at a specific point in time.

The income statement (P&L statement) focuses primarily on a company’s revenues and expenses, focused on a specific time interval. Here expenses are subtracted from revenues, and the resulting statement represents an entity’s overall profit figure which is referred to as “net income.”

The cash flow statement (CFS) measures how well a company generates cash to fund its debt obligations, cover its operating expenses, and fund additional outside investments.

Assisting the Small and Medium Business

Need more help? Independent web resources such as the Capterra Small Business Software Site offer great options for completing research and analysis on available solutions, some even offering complementary assistance and matchmaking services to pair your needs with a wide range of offerings. Most providers deliver accounting system products that range from the basics required by a sole proprietor to the sophisticated demands of complex businesses, many with increased scalability and growth in mind. Some include project management capabilities, collaboration functionality, and workflow, so a good first step is to understand all your fiscal, operational, and process essentials- now and looking forward. For reference, and in alphabetical order, some accounting software solution vendors and their products include but are not limited to:

Note: These company/product descriptions have been extracted from individual vendor websites. They do not imply endorsement or preference.

There are four groupings for reporting: cash, liabilities and shareholder equity, revenue, and expenses.

Typically included, per the previous reporting list, are assets, liabilities, equity, revenue, and expenses. Each of these is broken down into sub-categories to further articulate more granular characteristics.

These include the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flow. Read more about each of these earlier in this document.

These are divided on a positive/negative scale- assets include bank accounts, real estate, prepaid expenses, and accounts receivables. Liabilities include obligations such as accounts payable, loans, credit card debt, and other due outbound expenses. Liabilities may often have a “payable” descriptor (i.e., AP) attached to them.

The point of tracking account data is to provide a basis for fiscal comparison over time. This is the best way to ensure accurate information is used in making business decisions that drive overall growth.

The COA is a listing of all existing accounts including a description of the specific use of the account. The GL contains the financial records of the organization, including the COA, and maintains the debit/credit balance information.

Access the previously referenced link to a list of representative solutions for small and medium businesses. Accounting software will provide a spectrum of capabilities and functionality, designed for a better view of fixed assets and liabilities.

A well-organized and descriptive COA can assist bookkeepers, accountants, and financial management of all types to be confident in their business decisions relying on accurate, timely, and relevant information. While with most business processes, here one size does not fit all, and the COA will and should evolve, enabling a greater and more customized view into the true revenue and expense realities of your organization. It also provides external parties with a snapshot view of an organization’s fiscal health for prudent investment, purchase, or approval of credit.

Courtesy of Investopedia with author additions:

Accounts payable is an account within the general ledger representing a company’s obligation to pay off a short-term debt to its creditors or suppliers. It can be viewed simply as an IOU to another supplier or vendor.

Accounts receivable, aka AR, represents the balance of money due to a firm for delivered but unpaid goods or services delivered to the customer. They appear as assets on the balance sheet.

The asset ledger is the portion of a company’s accounting records that detail the journal entries relating only to the asset section of the balance sheet. Assets represent resources with economic value anticipated to deliver future value to the organization.

A balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a specific point in time. It provides a snapshot of an organization’s financial health and worth.

Cost of Goods Sold, or COGS, represents the total expense to produce a product or service. It normally includes direct costs such as parts, materials, and labor, but does not take into consideration indirect costs such as distribution.

Financial statement analysis, logically, is the process of analyzing a company’s financial statements for decision making purposes, given overall performance, adaptability to business trends, and the ability of management to execute on strategy.

A general ledger represents the record-keeping system for a company’s financial data with debit and credit account records validated by a trial balance. This information is used to create financial reports and to rate corporate fiscal performance over time.

These represent the situation when money is owed to another party. Obligations can be filled through the transfer of funds or the provisioning of goods or services to cover the debt. Both short-term (typically less than a year) and longer-term liability accounts exist.

Usually the final line (aka the “bottom line”) of any income statement, Net Income is comprised by subtracting all business expenses and operating costs from total revenue. It is most often used to assess enterprise health and is a determinator of business loan eligibility.

Shareholder equity (SE) is the owner’s claim after subtracting total liabilities from total assets; it represents the net worth of the business. It articulates how much owners have invested, and on the balance sheet is divided by common shares, preferred shares, and retained earnings.